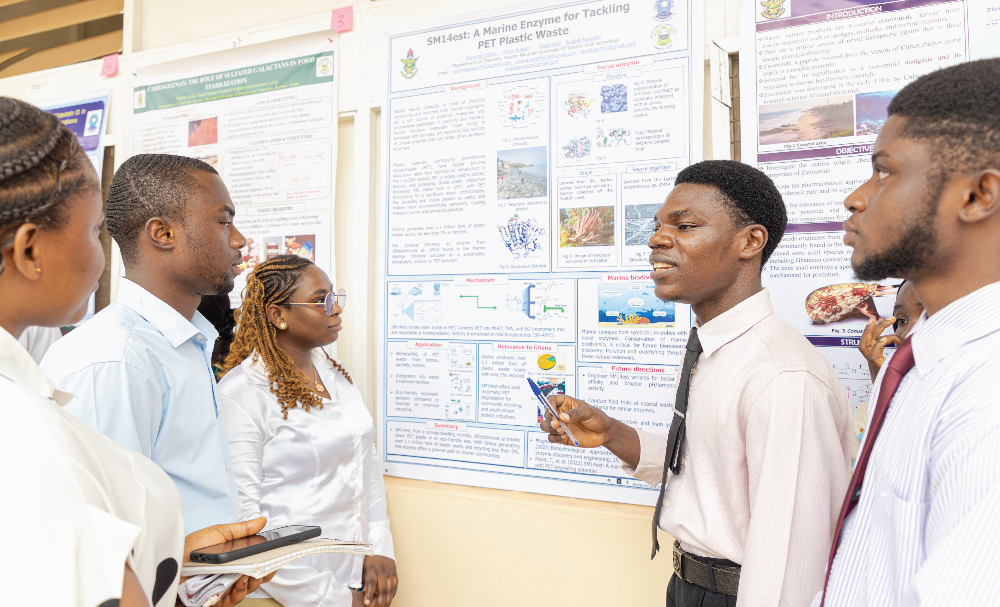

A team of chemistry students at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi are exploring how a marine-derived enzyme could help combat the country’s growing plastic waste crisis.

The student-led study investigates how a microscopic enzyme extracted from sea sponge bacteria can break down one of the world’s most persistent pollutants: polyethylene terephthalate (PET), used in plastic bottles and wrappers.

The project forms part of the Department of Chemistry’s Marine-Derived Natural Products course, which explores the potential of marine organisms in pharmaceutical, industrial and environmental applications.

The enzyme, SM14est, is sourced from a microbe found in Haliclona simulans, a sponge species native to Ghana’s southern coast. The students demonstrated its ability to degrade PET into smaller components that are easier to recycle or biodegrade.

Team members include Ebenezer Tetteh, Angela Assiadan, Oliver Acquah and Obed Kyei.

“Our goal is to find a way to break down plastics without harming the environment,” said Tetteh. “Current chemical methods often release toxic gases, so we end up solving one problem while creating another.”

He said marine enzymes offer a safer, more sustainable solution.

Ghana generates over 1.1 million tonnes of plastic waste annually, but less than 5% is recycled. The remainder clogs drains and waterways, contributing to flooding, pollution and public health risks.

The students said their work goes beyond laboratory experiments, aiming to support community-based recycling systems and educational outreach programmes.

“By tapping into our marine biodiversity, we’re showing that Ghana has the potential to lead in clean technology,” said Kyei.

The team hopes the enzyme can be modified to work efficiently in Ghana’s high temperatures, making it suitable for local recycling initiatives.

| Story: Edith Aravor (URO) | Photos: Emmanuel Offei (URO) |